I was recently invited to give a student lecture on healthcare as part of an ongoing series by DESINELab here in Rhode Island School of Design. I wanted to share what I talked about here in this blog to extend the conversation to a wider audience. Any kind of feedback or comments would be much appreciated.

My interest in healthcare was sparked in an advanced studio class I took with Nathan King and Olga Mesa called Future Health Systems. In this class, I realized that most of my personal efforts in trying to affect positive change, within systems like business, the food industry, agriculture, and education were all connected with healthcare, or at least my own vision of healthcare. For that studio, I proposed an ideal healthcare system for the Philippines through architecture, which you can find here. I am currently writing a manifesto for it, in the hopes of making it a reality.

This narrow focus on a specific area of design has opened many doors for me. I recently did an internship in MASS Design Group, as one of the first RISD students to do so. I have been asked to start consulting with a group of doctors in Manila who are building about 40 hospitals and clinics across the country. The pace of my understanding and knowledge on the field has been increasingly fast due to my niche interest in specializing coupled with the demand of good designers in the field.

Paradigm Shift in Healthcare

Healthcare has long been ignored by the majority design community. Yet, it is currently experiencing a paradigm shift in where designers are crucial components. This shift is in response to a universal effort of decentralizing and defragmentizing traditional healthcare: from reactive to preventive, from medicine to wellness, from the hospital to the home, from the wealthy to the masses. Therefore, the definition of healthcare is as complex as ever.

Traditionally it is defined as the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease, illness, and other physical and mental impairments in human beings. However, a lot more attention has been focused on just diagnosis and treatment. It is traditionally delivered within primary, secondary, and tertiary care, as well as public health.

However, projecting forward this definition, as I have mentioned, will change. Therefore, looking forward, my own definition of healthcare is the maintenance of a persons complete wellness system, which includes social, spiritual, physical, occupational, intellectual, emotional, and environmental.

For this lecture, I will be using the lens of architecture in talking about design in healthcare but I want to emphasize that any field of design is just as important. To help understand the current context of healthcare architecture, I want to quickly talk about its history. Just like design movements, healthcare has gone through several revolutions since its inception.

Prehistory of Western Hospital Architecture

Prehistory of Western Hospital Architecture began in Ancient Greece where the concept of health was closely linked to religious rites and rituals. It emulated the model of their classical temples. In the middle ages, monastic hospitals were built that resembled monasteries like Hotel Dieu. Most hospitals until the 1700's were designed in parallel to the architecture style of their time. They were rarely designed with the pure intention of being a place for treatment. In the renaissance, hospitals were designed according to the geometrical principles that were popular at the time like the Ospedale Maggiore in Milan in 1468. Then in the 70's western countries started producing statistics that triggered the first revolution in hospital design

Ancient Greece

Middle Ages

Renaissance

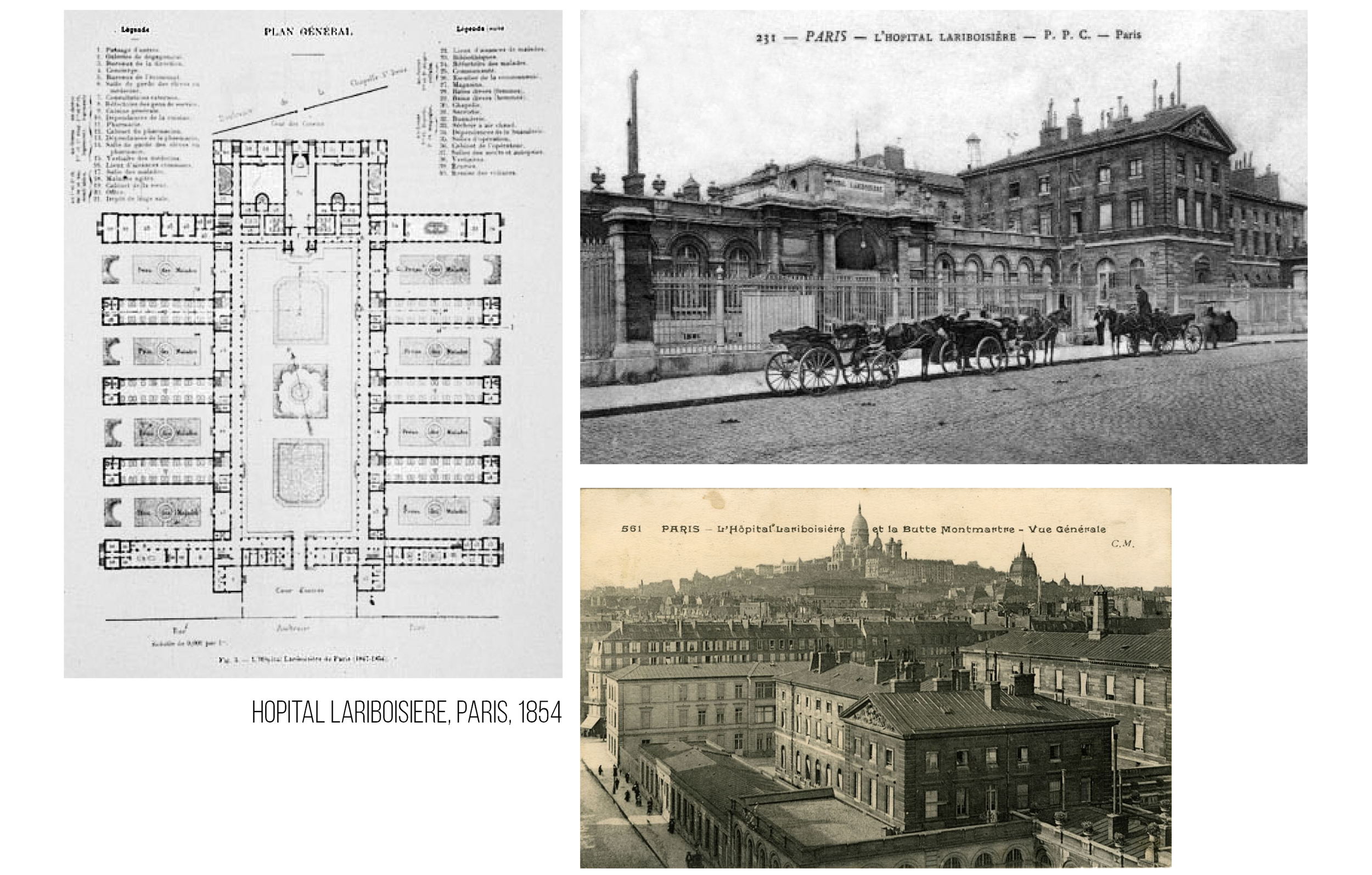

First Revolution: Built Natural Healing.

Hospitals were the first buildings that were completely determined by scientific and philosophical concepts. It was inspired by the poor outcomes of existing hospital designs that pushed designers to rethink hospital design. Two concepts were brought forth in Paris: the radial system and the pavilion system. Both systems believe that healing is not derived from medicine but from being in a purified, natural environment that provided clean air. The Hopital Lariboisiere by M.P. Gauthier built between 1839 and 1854 is credited as the first pavilion hospital. Pavilions maximized sunlight and windflow. Apart from designing hospitals using the beneficial effects of nature, architects designed hospitals to become iconic. By housing medicine in such a way, it influenced the public to believe that it was important and thus provided more investment, which drove medical science.

Second Revolution: Medical Science and Technology.

At this time period, we begin to see the shift from using nature to using technology. This shift in balance began with the invention of the x-ray. Pavilion type hospitals were replaced with block hospitals because they thought long corridors made it more inefficient. Block hospitals were good for centralizing common utilities like the x-ray which was too expensive to place in every building/pavilion. The first of this block type was the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York by James Gamble Rogers built in 1930. However, with the introduction of the block type, we lost an essential architectural feature: the ambition to create healing environments that emulated nature.

Third Revolution: Hospital for the Masses.

This revolution was the product of WWII and the 'social revolution' which fostered the idea of the Welfare State. Social Security Systems were set up in most countries to safeguard the public from unemployment, disability, old age, and illness. Due to the influx of new patients, technology was focused on treatment facilities and outpatient wards. Hospital architecture became synthetic and a new type of hospitals emerged called Matchbox on a Muffin Type. The idea with this new type was that it is much easier to rebuild and redesign the ground floor than to make changes in high-rise buildings. It combines a flat spreadout building and a high rise building containing the patient ward on top. It allowed changes to occur without disturbing the patient wards. The first of this type was the Hopital Memorial France-Etats-Unis in Saint-Lo by Nelson in 1956. Since hospitals were now open to a larger population patients stopped being treated as people but collection of possible diseases or just data. This ran parallel with the capitalistic trend of the Western culture and the rise of bureaucracy.

Fourth Revolution: Empowering the Patient.

Hospital embodies conflict between the individual, and the needs of the medical staff and equipment. This led to the invention of a neutral, industrially-built, unexpressive structure that was no longer recognizable as an individual building. An example of this would be the Medical Center of Groningen in the Netherlands which emulated the city by introducing covered streets, a huge hall, and many shops and restaurants. Unfortunately, The transition from a medicine-dominated to a management-dominated hospital has not curbed the process of institutionalization. It failed to return the hospital to the people. Technology and science that was once the main justification for hospital architecture and design is now what is driving it to the opposite direction.

Fifth Revolution: Returning the Hospital to the People.

This revolution should initiate the return to the basic principles of decent management, empowerment of the patient, de-institutionalization, and the courage to re-conceptualize healthcare and to let it go back to its core business. We are the generation currently undergoing this paradigm shift. Healthcare is shifting from being purely reactive to preventive, but we still have a long way to go.

Designing Forward

How can we design for this new shift towards preventive healthcare, or what we can even call responsible design? I believe the answer lies in research and evidence-based design. When I interned in MASS Design Group, I learned that there should be 4 stages in design. Traditionally especially in architecture, there are two that we mostly focus on: Design and Construction or Manufacturing. However, there should be two more stages to make design more efficient and effective.

Prior to the design phase, there should be a pre-design phase in where you research the context holistically. RISD design students are very aware of this and most of us approach projects this way anyways. However, where I think we are lacking are looking at things from a systemic point of view. Here is where ID students do better than architecture students in my opinion. In architecture, we often use the pre-design phase as basis of form and program making, which I think is still very shallow. Pre-design must be thought of from the scale of systems all the way to the people that use the system.

The fourth phase goes after construction or manufacturing called Impact Analysis. This is often very difficult to do because it costs money outside the traditional budgets that are given by clients. However, it is one of the most important phases because it teaches the designer what actually works and what doesn't outside the theoretical realm. Without Impact Analysis, we cannot achieve a complete feedback loop and that is why history of design has been so inefficient and ineffective. We are currently designing objects and buildings without considering what kind of futures they will create both environmentally and socially. This is a manifestation due to the lack of impact analysis of our designs.

With all 4 phases completing a feedback loop, designers can truly achieve research and evidence-based design. This means that your design is an efficient use of resources because your design meets a real need and demand rather than a theoretical one. From this we can start designing an environment that actually suits our human needs and prevent us from being unwell and getting sick. We cannot use money anymore as an effective way to gauge the flow of resources. Why not try using wellness as a metric of developing a project and as a way to see its following success?